the persistence of memory

Fall of Babylon

We emerge from the ranks of rocky hills dressed in bright spring wildflowers the way a night sky may be studded with stars well after midnight. Sea fog rises and falls, and the Atlantic coast of western South Africa is still invisible, but we can see mounds of tailings stretching for miles. A mine. We poke around a seemingly empty building — a guard station? — until two uniformed security guys show up. Yes, a mine. Diamonds. And another company town, hushed against the ground, barely lit, subdued. Miraculously, the guys let us stay in the mine’s parking lot and spend the night.

“Do you live in Alabama?” one of them wants to know. I tell him no, and he sights: “Alabama…” “Have you been there?” I ask. “No,” he says, “but I watched a TV show. From Alabama. I liked it.”

We park, and before we cook our nightly soup we have visitors. Two tiny owls perch in the tree above our camper and then screech their way to the nearest roof and sit there, little hunchbacks with pointed Leonard Nimoy’s Vulcan ears. The fog eats the land, traps the day’s warmth, and holds it till the daylight returns many hours later. We roll on to the coast.

Hondeklipbaai. What is this collection of dwellings held together by tin and old paint, and a few better cabins with blue trims? The place seems to speak of little money and much struggle to hold on. Is it a fishing village? Surely not, what with its piss-poor harbor, barely protected by a few coastal rocks and smacked hard by every wave which happens to show up. A vacation spot? Again, not with these shanty-flavored outhouses, two deserted campgrounds and bumpy gravel roads ending mostly nowhere, even though the community —

with tiny patches of gardens and no trash anywhere — is not unloved.

But we are wrong. A man we ask says it is both, and more: it is also a mecca for men diving for diamonds. Does he fish? Yes, for lobster, but the government makes it harder than ever by cutting fishing quotas to the bone and allowing big boat boys to have their heyday. Does he dive for diamonds? Yes. How deep? Down to 18 meters. Dry suit? No. But the sea is cold, we say, and suddenly understand the wet suit he obviously uses is not his choice: it is what he can afford.

We need drinking water, so I pass the harbor with its diamond diving boat and several bobbing skiffs, and head for a funky coffee nook, one of the few establishments in town. The owner is blond and very helpful. She does not have much water to spare but will let me have some, except I may not like it. Is it bad? I ask. Well, it is brack, she says, and some folks get sick from it. She has a small filter she uses but I have been already battling my African intestinal unrest three times and will skip her brackish water unless we run totally dry.

Her tiny open kitchen is crammed with paintings. Yes, she paints, and the whole dusty outdoor gallery is hers and her husband’s. We

talk. I feel my brain slipping into my old “just listen” journalistic mode as easily as my feet slide into my old hiking boots. Her name is Madelaine but she did not like being called “Mad” and added a “z’ to the end: Madz. Madz the artist, from Hondeklipbaai, South Africa.

I take her picture . “Should I hold a brush?” she asks, and I say yes. Then John and I eat her breakfast food, a toastie with slices of ham, tomato and cheese. We hug. She gives me her business card. It is all so simple and unforced I want to sing.

Outside I bump into her man, Deon. Red face, small pony tail, quick, followed by a posse of dogs. I tell him I like the paintings in the yard, and he informs me they sell from as little as 500 rand to as much as 2,500 for the big ones. Some go to America, and one just went to Iceland. Wow, I say, and he invites me to his studio, a tiny white trailer half buried in blossoming flowers and half occupied by a bed which has not been made for a while. He tells me he never invites anyone in, not even his wife, because he likes to be antisocial there and just paint. But now he just talks.

I listen, and feel as if the last three months of watching great African animals abruptly ended and I was now among my own herd, attuned to its needs to be heard and understood. Deon tells me about his early painting days when he just played with pictures and moved all around the country. And then about his five years in prison and two out on parole. Armed robbery. Some fellow owned him a chunk of money but would not pay back, so Deon went and took what he could. Had a gun. Got caught.

My eyes slide away from his easel with a bright seascape under construction and move onto a wall. A nude, standing by a chair. Red hair. Dark nipples. Great composition. “Oh, she was my social worker in prison,” Deon says. “No, she did not pose naked. One day, she came into my cell — it was really tiny — and I suddenly saw her like this. And here she is, just as I saw her.” He says that after the prison he just wanted to hide and have a quiet life by the sea. Came here. Got to paint a lot, to sell. Met Madz on Facebook. In a few years, he wants to be one of the best 10 painters in the world.

He watches my eyes really closely now, and follows them to a painting sticking out of a pile of seascapes sitting by the door. I can make out some vague outlines of monumental structures collapsing as if under their own great weight and a pair of bare breasts. But there is more. Deon dusts the canvass off and slaps it extra hard to get rid of some grit I cannot detect. “This one,” he points to a woman in a on top of the picture, “is my ex-mistress. And this one is my ex-wife. They both just cut my head off — see?” I see: it is his head, long haired, bloody, inert. And then he adds: “I call it Fall of Babylon.”

We leave the studio. Shake hands. The sky begins to brighten. I will send him the pictures I took. And he can be antisocial again and just paint. Maybe more landscapes, maybe his life. Whatever comes next. ©Yva Momatiuk

not here

Quiver trees — also known as kokerboom — thrive in the southern Namibian desert.

talking to animals

Not today, but maybe soon. ©Yva Momatiuk

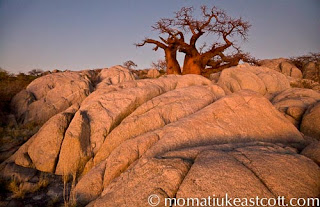

Makgadikgadi Pans

Kubu Island, Botswana

lynx

We are back in Alaska, falling silly in love with animals we meet.

First, there are red foxes, three kits as bright as new flames, tumbling across the road on Denali’s Polychrome Pass at daybreak. It turns out the things you can d…

processionary life

Round and round we go in the red hot center of Australia, circling the monolith of Uluru – once known as Ayers Rock – while looking for chinks in the armor of the rules governing Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. We want to walk away from t…

birthday animals

I am walking on an old logging trail which branches off Lower Cache Road, a tributary to Alaska Highway in British Columbia. Thin strands of morning fog soften scraggly black spruce and float among white aspen trunks. A long…

beach

This morning the ocean is almost still, with small whitecaps rising here and there in lazy intervals, as if reminding itself of its sleeping power. Last night, every southern star basked in a faint moonlight glow and the mountains stood dark and blue-h…